Kanazawa Castle: Hokuriku’s Horizontal Hold

Say “Japanese castle” and most picture the mountain-like layers of Himeji or the stately dark facade of Kumamoto. But, like their European counterparts, Japanese castles vary widely in shape and construction. Each reflects the materials and technology of their day and the defensive needs of their political realities.

Those with tall and imposing keeps catch tourists’ attention, but the less attractive castles often hold more interesting secrets. And Kanazawa Castle is no exception.

But is it worth the ticket?

Most of Kanazawa Castle Park is free, but the central-most complex of the turrets, storehouse and central gate require a ticket of just a few hundred yen.

Some overseas visitors may turn away from Kanazawa Castle for a lack of a keep. But my friend Hiroki says Kanazawa has more of a castle than Osaka, his hometown. What makes a castle, he says, is the space, and no Japanese castle is complete without a garden!

So if you’re already planning a trip to Kenrokuen Garden, the “Kenrokuen +1” ticket is worth picking up. You’ll get a proper “Japanese experience” of seeing the surrounding land from a samurai’s point of view followed by a garden stroll worthy of royalty.

Consider what makes Kanazawa Castle special:

- It’s one of the largest wooden structures surviving since the Meiji era.

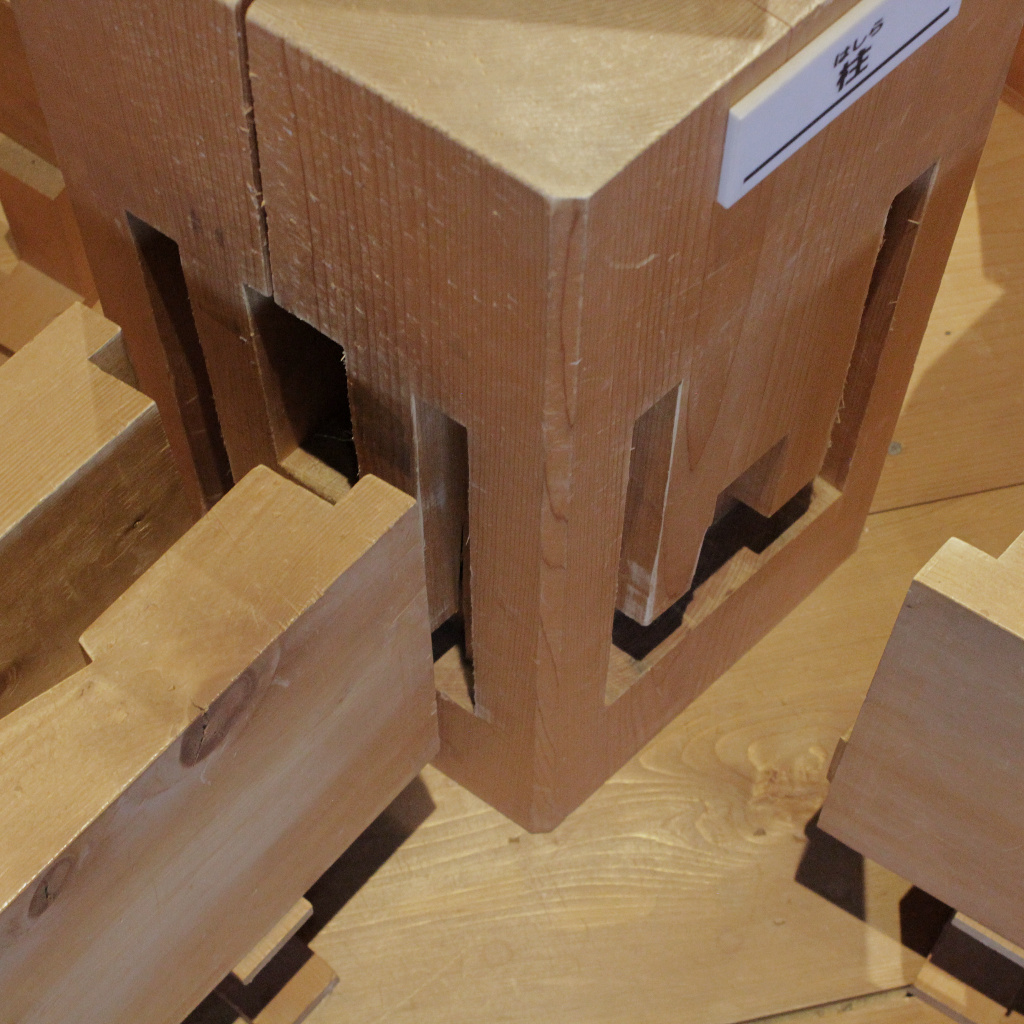

- It’s constructed entirely using traditional wooden joint techniques, without a single nail or bolt!

- The Hishi Yagura (“diamond turret”) is built, not with right angles, but odd angles that had to be carefully constructed by hand. The slanted room allows the best few of the gates on three sides for lookouts to watch.

- It has an unusual horizontal design, which the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art also imitates.

- The outer turrets are adorned with a namako tile pattern in a very rare “straddled joint” style.

- It has the greatest variety of stone walls of all Japanese castles.

Still not sure? Test yourself with a visit to the fully restored Kohaku-mon Gate. The space is limited, but you’ll have a glance at some of the basic features of the castle’s defenses and architectural design. If it tugs at even the smallest bit of your interest, then the main complex will satisfy. (And if it’s the restorations that turn your nose, cross Kenrokuen Garden and check out the Seisonkaku Villa instead!)

Architecture lovers, carpenters, geologists and wartime history buffs, stick around!

Kanazawa Castle Design

Building & Carpentry

Other castles may have the height that makes for good postcards, but lovers of architectural design can find treasures in this pristine restoration.

Taking advantage of its position on the Kodatsuno Plateau, Kanazawa Castle is more wide than tall. Even in the decade when its six-story keep stood, the walls kept it far from the edge of the castle grounds.

Most of the wood used to restore the castle was lumbered locally. Each piece of timber is fitted with tongue and groove joints and without any use of metal, following the original carpentry techniques of the era.

The Hishi Yagura, the “diamond turret,” is particularly unusual in its angled design. Rather than the typical angles of 90 degrees, the entire tower is custom-built with angles of 80 and 100 degrees. It’s believed this allowed its third-story windows to have full views of each of the castle gates.

In both the central castle complex and the Kahoku-mon gate, visitors can find details of the castle construction. Fortifications are layered in the walls, and there are machicolations—“murder holes”—for dropping rocks on attackers.

Along the castle’s outer-facing walls, window positions alternate between floors, reducing blind spots among lookouts.

By contrast, along the inner-facing walls, windows are aligned for a more pleasing, uniform appearance.

Walls and Foundations

On the park grounds, upstairs inside the Kahoku-mon Gate and inside the larger complex, examples of the fortified walls’ anatomies are on display. Each layer of wood, mud, rope and plaster is carefully combined to be both robust and weather resistant.

Most stones which form the many styles of walls around the castle are igneous rock from the nearby Mount Tomuro. These blocks of andesite appear prominently in two varieties: red and blue. The latter is the denser and heavier of the two. Kanazawa Castle is rare among Japanese castles for featuring this motif in its stone coloration.

The stone wall styles are of the greatest variety among Japanese castles, including three styles of fittings. The extra tight kirikomi-hagi (“deep cut”) has the cleanest look. Nozumi (“piled up”) walls of uncut stones allow efficient draining. Uchikomi-hagi (“broken up”) walls are a happy medium.

The oldest stones at the castle bear the marks of the masons who brought them, etching their presence on the castle even today.

The History of Kanazawa Castle: Built for Battle, Felled by Fire

Deceptively bare, much of Kanazawa castle’s true history has been burnt and buried beneath its cement walkways. Its heights were brought low without a single scar of war. Rather—and as with much of Japan’s architectural history—Kanazawa Castle’s 300-year-long war has been with fire.

The castle has been set aflame six times over three centuries:

- In 1602, the castle keep burned down after being struck by lightning. (The keep is what many refer to when they say, “Kanazawa has no castle.” It has yet to be rebuilt.)

- In 1620, a fire started in a merchant’s home near the Sai River, spreading rapidly and taking over a thousand buildings down. The castle partly burned.

- In 1631, another devastating fire took out thousands of buildings, becomeing known as the Great Fire of Kanazawa. The castle partly burned again.

Thereafter, the Tatsumi Canal, one of Japan’s four greatest man-made waterways, was built to supply the castle with a steady supply of water, using siphoning pressure that works to this day! - In 1759, most of the castle was burned down by a large fire.

- In 1808, the palace in Ni-no-maru (the second ring) burned down.

This is area is the most recent to be walled off for excavation and study. - In 1881, a section of Ni-no-maru was burned down by a large fire.

The Hashizume-mon Gate, the main entry into the inner most courtyard and connected to the park’s main castle complex buildings, was built in 1631 after the Great Fire of Kanazawa. It was rebuilt three more times in 1762, 1809, and 2001, and the fourth one stayed up and still stands today.

The gabled gate at the back of Oyama Shrine once belonged to the inner sections of Kanazawa Castle. As part of the small section of Ni-no-maru that was not destroyed by fire, it was believed to have been protected by the water dragons in its carving.

Before the Samurai

Before the (seemingly ever-burning) walls of Kanazawa Castle were even erected, before the Edo era, before the daimyo and the much beloved Lord Maeda Toshiie, here stood the heart of Japan’s “Peasant Kingdom.”

After almost a century of internal disputes and civil war, a government unique to Japan formed. A theocratic feudal confederacy of farmers, peasants, priests and monks of Jodo Shinsu Buddhism (“True Pure Land Buddhism”) settled into a stable government. The capitol was a fortress known as “Oyama Gobo,” a name that still exists in part in Kanazawa through the nearby Oyama Shrine.

The Fall of the Peasant’s Kingdom

When the feudal warlord Oda Nobunaga began his conquest of Japan, the forces of the Peasant’s Kingdom put up such a fight that Nobunaga had to personally lead assaults into the region. His retainer, Sakurma Morimasa, destroyed Oyama Gobo itself, chasing the last of the confederates south to smaller strongholds in today’s Hakusan region, where they, too, were eradicated. Morimasa was granted the capital and began construction of what would become Kanazawa Castle.

After Nobunaga’s assassination, Morimasa had opposed Hideyoshi’s eventual rise to power, a choice that would lead to the end of his own life. Thereafter Kanazawa Castle was granted to Hideyoshi’s young general, Toshiie Maeda, whose march into the castle in 1583 is reenacted every year at the Hyakumangoku Festival.

Jodo Shinsu Buddhism was cast out from Kanazawa, and existing temples of other sects were pushed to more defensive locations throughout the city into three temple districts.

Utasuyama temple district sits just above the largest geisha district of Higashi Chaya. The plateau in the distance to the right is Kenrokuen Garden and Kanazawa Castle.

Utasuyama temple district sits just above the largest geisha district of Higashi Chaya. The plateau in the distance to the right is Kenrokuen Garden and Kanazawa Castle.

The Here and There of Daimyo Life

In the Edo era, daimyo spent little time administrating their domains or even living in their own castles. The Maedas may have been the Lords of Kanazawa and most of the Hokuriku region, but half of their years were spent off in the capitals.

Much of Toshiie’s time as lord was in Kyoto, securing that lordship and the means by which his decedents could increase Kanazawa’s wealth and holdings. His successors submitted time and significant resources to live in second homes in Edo—today known as Tokyo—to appease the ruling Shogunate. Even many of the lords’ family members were quickly married off or passed as hostages to other lords to ensure peace.

But the remaining family members and the administrators beneath the Maeda Lords still inhabited Kanazawa Castle proper.

Edo Politics and Tentative Peace

Under the rule of Toshiie and his eldest son, the Kaga Domain rapidly flourished, growing rich with rice production. This wealth, one million koku (around 150,000 tonnes or 5,000,000 bushels, total) of rice is still celebrated today in the phrase “Hyakuman-goku.”

However, at the time, it simply made the ruling Tokugawa Shogunate nervous. The alliance was reinforced with a marriage between grandchildren, Toshitsune and Tamahime. (The latter, then only a child bride, is still honored at Kanazawa’s Tentokuin Temple.) And the construction of the Tatsumi moat gave the castle extra defense, for which Toshitsune then had to send deep apologies and an explanation to the Shogun at Edo.

Despite Toshitsune’s insistence that the canal was only for irrigation, legend still says there is a tunnel connecting Kanazawa Castle and the “Ninja Temple” where a forbidden samurai army hid. And the castle itself functioning as a military storehouse with other defensive measures is in no doubt. Along with the “murder holes” above the castle moats, the lead roof could be quickly scrapped and melted into munition.

Changing Owners in a Changing Japan

During the Meiji Restoration, the samurai class was dismantled and daimyo systems dissolved. Kanazawa Castle and its lands fell into the hands of the government. In 1898, headquarters for the Army’s 9th Division were built on Kanazawa Castle’s grounds. (They have since been relocated nearby and function as one of the two connected buildings of the National Crafts Museum.)

In 1945, Kanazawa University was established with Kanazawa Castle as its campus, until it was moved in 1995. I can only imagine what it was like to study at a castle…

Thereafter, Ishikawa Prefecture procured the castle from the national government and has since begun full restorations of the buildings. The ground beneath is carefully excavated and building footprints unearthed. Artifacts from the castle are featured both inside the complex and at the finely preserved Seisonkaku Villa on the edge of Kenrokuen Garden.

While you’re there…

Kanazawa Castle Park is just across the way from Kenrokuen Garden Park. If attending both, pick up the “Kenrokuen Pluse One” discount ticket to save some yen.

Garden lovers should also check out the Gyokusen’inmaru Garden on the castle park’s west side. Unlike Kenrokuen, which is a strolling garden for guests, Gyokusen’inmaru was a private viewing garden. It’s best enjoyed from inside the tatami-lined rest house, with a bowl of matcha tea.

open every day, except New Year holidays (Dec. 29th – Jan. 3)

(may close for private events)

9:00 a.m. – 4:30 p.m.

matcha green tea wagashi sweet: ¥720

A number of events are held in Kanazawa Castle Park throughout the year, including a traditional Japanese falconry demonstration in February.

March 1 – October 15: 7:00 a.m. – 6:00 p.m.

October 16 – February 29: 8:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

Hishi Yagura, Gojukken Nagaya and Hashizume-mon (complex)

9:00 a.m. – 4:30 p.m. (last entry: 4:00 p.m.)

admittance: ¥320

wheelchair accessible and wheelchairs available upon request

About a decade ago Rachel fell off a bus and then fell in love with this traditional-crafts and ice-cream-consuming capital of Japan. Editor and amateur photographer with a penchant for nature and history. Not actually fifty songbirds in a trench coat. (Former penname: Ryann)