The Voice of Japanese Zen: D.T. Suzuki

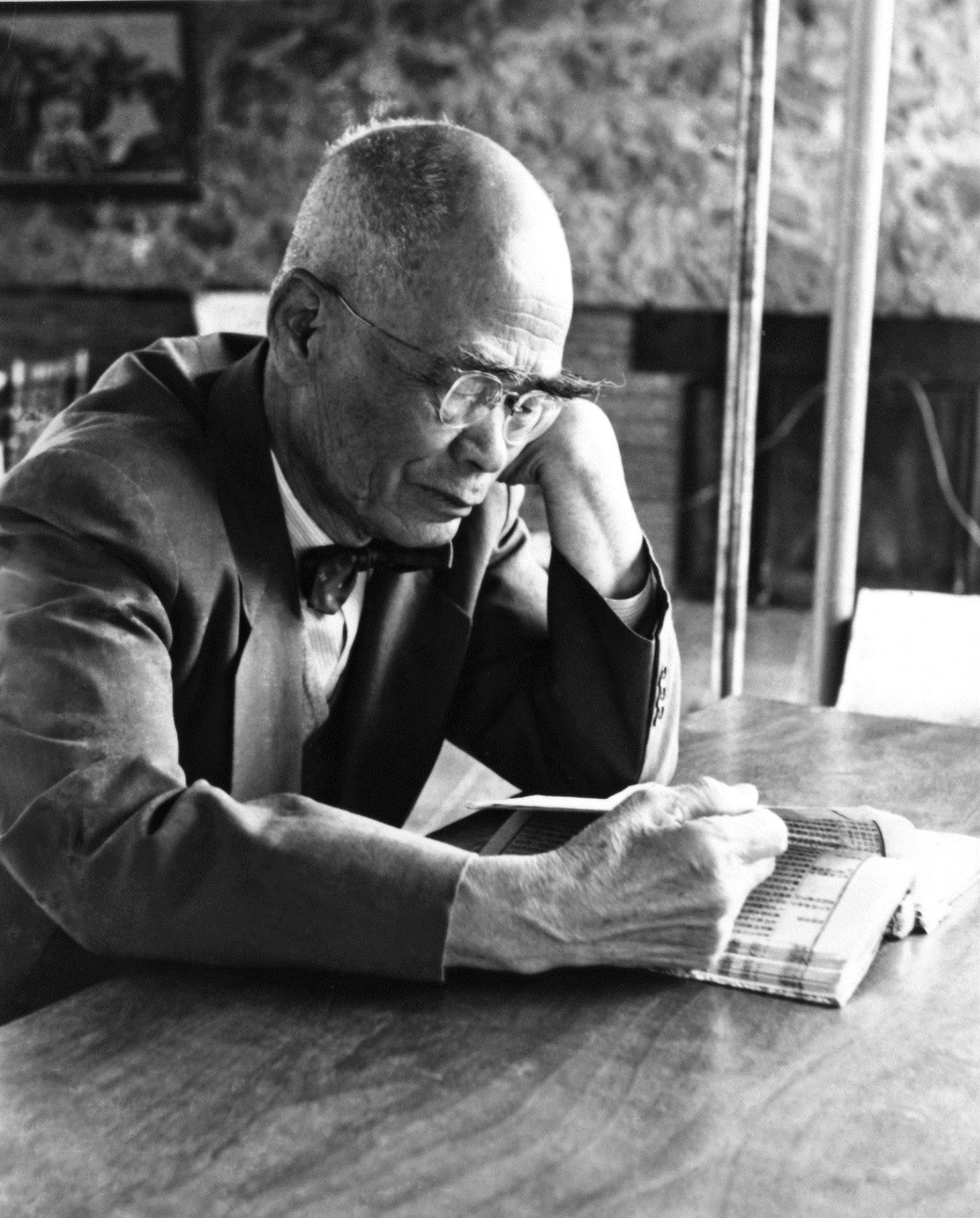

Suzuki at age 86 in Mexico; image courtesy of the D.T. Suzuki Museum

Suzuki at age 86 in Mexico; image courtesy of the D.T. Suzuki Museum

A Son of Samurai, a Life of Loss, the Voice of Japanese Zen:

D.T. Suzuki

A Most Difficult Childhood

Unless we agree to suffer, we cannot be free from suffering.

When he was only six years old, little Teitaro Suzuki, the youngest of five children, lost his father. A year later, he lost an older brother.

Born into the beginning of the Meiji Restoration, the Suzuki home had gone from the esteemed physicians of the Honda Clan, the second grandest samurai house in the castle town of Kanazawa, to abject poverty with the abolition of the samurai class.

The ego-shell in which we live is the hardest thing to outgrow.

The youngest Suzuki chased down monks and missionaries alike to debate philosophy in an attempt to understand his own difficult circumstances. While attending the Ishikawa 4th High School, he befriended Kitaro Nishida, who would become one of Japan’s most influential philosophers. The mathematics teacher engaged his discussions and piqued his interested in Zen, but the financial deterioration forced him out of school and into working life teaching English.

A young Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki; wikicommons

A young Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki; wikicommons

His mother passed when he was only twenty. A year later, one of his older brothers financed his way into universities in Tokyo.

Translations and Transcendence

Zen teaches nothing, it merely enables us to wake up and become aware. It does not teach; it points.

While at university, Teitaro Suzuki studied Chinese, Pali, and Sanskrit. He also began visiting the nearby Engaku-ji Temple in Kamakura regularly, eventually taking up residence there. The temple’s headmaster, Soyen Shaku, was to be Zen’s representative in the first World Parliament of Religions, a dialog of faiths from around the world. And it was Suzuki who translated Shaku’s address into English for the extraordinary event.

The connections made at this conference gave Suzuki more translation work while he continued to study Zen at the temple, and, five years later, he would travel to the United States to work on a translation of the Tao Te Ching.

Until we recognize the self that exists apart from who we think we are, we cannot know the Zen mind.

Shortly before his first of what would a twelve-year journey overseas, Suzuki achieved enlightenment and received his new name, Daisetsu (often penned Daisetz in English), meaning “great simplicity.”

In the United States, Daisetz Suzuki continued to study languages, translated Buddhist texts, served as Shaku’s interpreter, and published his first original book in English on Buddhism. Before his return to Japan, he visited Europe and England for more research and translation work.

Technical knowledge is not enough. One must transcend technique so that the art becomes artless, growing out of the unconscious.

Suzuki became a university professor and a husband to theosophist Beatrice Lane. After Shaku’s passing in 1919, the couple moved to Kyoto, where Suzuki continued to teach, compose essays, and give lectures abroad, including one that inspired a young Alan Watts.

Dark Times Return for Suzuki, as Does Light

Unless we die to ourselves, we can never be alive again.

When his long-time collaborator and wife, Beatrice Lane Suzuki, passed in 1939, Daisetz went into seclusion in Kamakura. By the following year, his books in England had gone out of print.

Five years later, the 1945 firebombing of Tokyo destroyed all remaining copies in Japan.

The skylight in the Contemplative Space of the D.T. Suzuki Museum, in the infinite shape of a circle.

The skylight in the Contemplative Space of the D.T. Suzuki Museum, in the infinite shape of a circle.

But Suzuki was not without support. Christmas Humphreys, a lawyer and founder of the London Buddhist Society, visited Suzuki the next year and worked with him to recover and re-translate much of the lost text. The current Essays in Zen Buddhism, originally published in 1927, resulted from the tireless collaboration.

The truth of Zen is the truth of life, and life means to live, to move, to act, not merely to reflect.

In 1949, Suzuki returned to lecturing, this time in Hawaii. A year later he was teaching again, in Hawaii, then California, and then New York, where his students included psychoanalysts Erich Fromm and Karen Horney and composer John Cage (of 4’33” fame), all of whom cite Suzuki as an influence in their work.

His last 15 years were spent in the care of his Japanese-American secretary and editor, Mihoko Okamura, and her family. He continued lecturing in various parts of Europe when not at their home in Manhattan, New York.

I am an artist at living—my work of art is my life.

Suzuki continued to live a long and healthy life, passing at the age of 95.

The Legacy of an International Zen Master

I am Japanese and aspiring to be a citizen of the world.

Several biographies have been written about D.T. Suzuki, and no discussion of Zen in the modern world is complete without him. He often expressed interest in socialist ideas and skepticism of government propaganda, even during the second World War. Risking arrest but protected by the revered station he had earned, he spoke against militarization (a point on which, infamously, not all Japanese Buddhists of the time agreed), according to Okamura.

Until Suzuki, Japanese Zen was believed to only be understood in Japanese. Through his experiences and learning, he determined to share Zen Buddhism in the lingua franca of fellow academics. He spent a quarter of his life living abroad, and more than a quarter with his American wife. He was especially fluent in English, even preferring to talk to his cat in this second tongue during his later years.

Outwardly, be open; inwardly, be deep.

His life and philosophy can be understood at least in part with visits to the D.T. Suzuki Museum in Kanazawa, the town of his birth. The museum’s very construction is a shrine to the man, designed with Zen philosophy and built with local resources, and it as well protects a camphor tree that stood while Suzuki was still a boy. Much of his extensive bibliography in English and Japanese is freely available to read in the museum’s library. The museum’s Water Mirror Garden can be enjoyed as a place of personal meditation with or without a ticket to the museum proper.

D.T. Suzuki Museum

9:30 – 17:00 (5:00 p.m.; last entry 30 minutes before closing)

310 yen entry

850 m (approx. 11 min. walk) from Kaname Inn Tatemachi

photos not permitted

All quotes are Suzuki’s, original or translated.

About a decade ago Rachel fell off a bus and then fell in love with this traditional-crafts and ice-cream-consuming capital of Japan. Editor and amateur photographer with a penchant for nature and history. Not actually fifty songbirds in a trench coat. (Former penname: Ryann)